Solar company First Solar forgoes deep-sea mined minerals due to shareholder demands

In the depths of the world's oceans, the future of deep-sea mining remains uncertain. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), responsible for regulating mining in international waters, is still in the process of finalizing the "mining code," a comprehensive set of rules and regulations for the extraction of minerals such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese - critical for green technologies and electric vehicles [1][3][5].

After a detailed review of the proposed mining code, which contains 107 regulations, the ISA's executive council has made significant progress. However, key disagreements remain, particularly concerning environmental protections and a fair, equitable framework for regulation [1]. Some member states, including Chile and 36 others, have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until there is sufficient scientific knowledge of environmental impacts and a robust regulatory framework [1].

The ISA's Secretary-General Leticia Carvalho emphasizes that the draft mining code is intended to balance resource extraction with environmental sustainability and global equity, as the deep seabed is considered a "common heritage of mankind" [3][4].

However, pressure to fast-track deep-sea mining, particularly from the United States, seeks to expedite the permitting process through national agencies like NOAA and potentially bypass ISA approval processes [2]. The Metals Company, which holds exploratory permits issued by ISA, has announced plans to invoke the "two-year rule" to apply for a mining license as early as June 2025 and is exploring mining under U.S. jurisdiction rather than waiting for ISA rules to finalize [2].

As of August 2025, the ISA has not yet finalized the mining code. Commercial deep-sea mining in international waters has not yet begun, as the code is essential to provide the legal and environmental framework before exploitation can commence [4].

In a positive development, First Solar, a solar manufacturer, has committed to exclude minerals mined from deep-sea production and supply chains due to environmental concerns. As You Sow, a shareholder advocacy group, negotiated this agreement with First Solar. This move is seen as leading the way in ensuring that the energy transition doesn't create another globally destructive practice [6].

As You Sow is also engaging with companies in key sectors to implement sourcing policies that exclude deep-sea mined minerals. The group has refiled proposals at General Motors and Tesla asking the companies to implement sourcing policies that exclude deep-sea mined minerals. This marks the fifth deep-sea mining withdrawal agreement in 2025 [7].

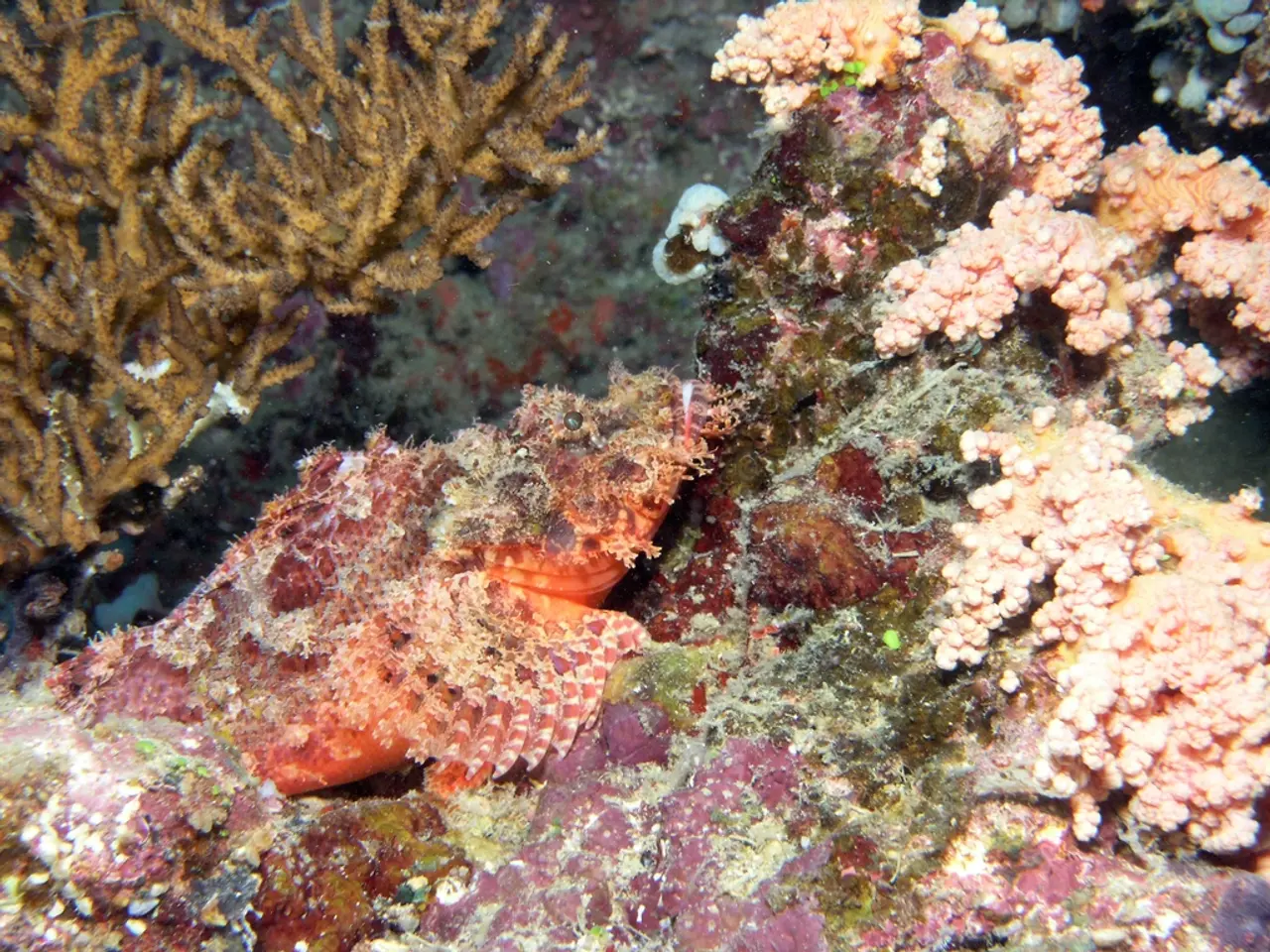

The growing number of agreements for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, with 60 companies and 30 countries on board, contrasts with rumours suggesting the seabed mining industry might receive a boost from the Trump administration [8]. The mining process of deep-sea trawling indiscriminately destroys sea life and ecosystems, releasing sediment plumes laced with toxic metals, causing a cascading effect of biodiversity loss [4].

As You Sow argues that companies must prioritize building a circular economy instead of engaging in environmentally destructive mining practices. Elizabeth Levy, biodiversity program coordinator at As You Sow, states that First Solar's commitment to exclude deep-sea mined minerals challenges a false narrative [9].

This critical moment shapes the future of deep-sea mining governance, where regulatory, environmental, and geopolitical considerations intertwine [1][2][3][4][5].

[1] https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-53527725 [2] https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/us-deep-sea-mining-firm-metals-company-says-may-apply-license-2021-06-02/ [3] https://www.devex.com/news/deep-sea-mining-is-coming-but-who-will-benefit-96710 [4] https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-52915225 [5] https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/deep-sea-mining-is-coming-but-who-will-benefit-96710 [6] https://www.asows.org/press-release/first-solar-commits-to-sustainable-minerals-sourcing-policy-excluding-deep-sea-mined-minerals/ [7] https://www.asows.org/press-release/as-you-sow-encourages-tesla-to-adopt-sustainable-minerals-sourcing-policy-excluding-deep-sea-mined-minerals/ [8] https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/us-deep-sea-mining-firm-metals-company-says-may-apply-license-2021-06-02/ [9] https://www.asows.org/press-release/first-solar-commits-to-sustainable-minerals-sourcing-policy-excluding-deep-sea-mined-minerals/

- The balance between resource extraction and environmental sustainability in deep-sea mining is a crucial aspect of workplace-wellness and health-and-wellness, as the health of the environment directly impacts the health of the global population and future generations.

- As the crisis of climate change continues to unfold, it is essential for the environmental-science community to advocate for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until a comprehensive, science-based regulatory framework is established to prevent irreversible damage to the ocean ecosystem and its biodiversity.