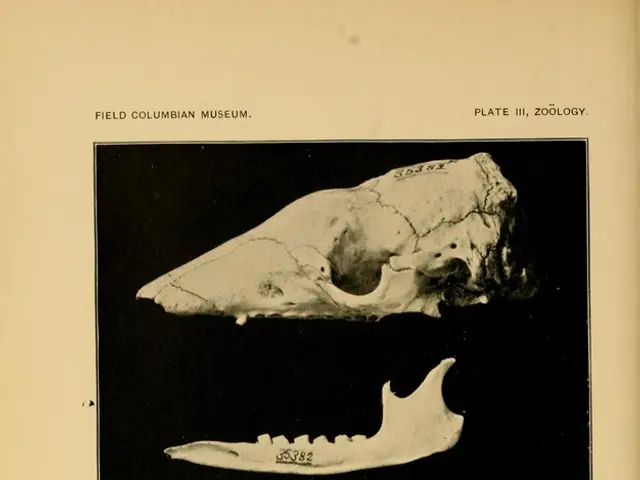

Pythons can consume bones due to distinctive stomach cells capable of dissolving bone tissue.

In a groundbreaking discovery, a team of zoologists led by Jehan-Hervé Lignot at France's University of Montpellier have uncovered a unique adaptation in Burmese pythons that allows them to effectively digest whole prey, including bones, and extract essential nutrients.

The researchers, using light and electron microscopy, studied the intestines of Burmese pythons and discovered tiny, unidentified objects along the snake's intestinal lining. Upon further investigation, they identified these particles as calcium, iron, and phosphorus within a newly identified type of cell. These cells, located deep in the snake's intestinal lining, are specifically adapted to process the minerals found in bones.

These particles reside in a "crypt" inside these narrow, specialized cells. The presence of calcium, phosphorus, and iron spheroids in python cell crypts was observed when snakes were fed bone-in rodents or a calcium-rich diet. Notably, pythons lacking these calcium- and phosphorus-heavy particles were observed when fed boneless food.

This remarkable finding sheds light on how Burmese pythons, such as the Burmese python (Python bivittatus), can digest calcium-rich skeletons without any issues. The team's research, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, also indicates that this bone-digesting cell has been identified in multiple python, boa, and Gila monster species.

An average wild python can digest a prey that is more than 30% of its body mass. Bones, which represent about 9-10% of a human body's weight, imply a significant amount of ions from the prey's skeleton can be absorbed. Remarkably, python droppings contained no bone fragments, showing complete dissolution of bones.

Lignot and his team were the first to find similar particles in vertebrates, not just insects and crustaceans. Though Lignot has since moved on to other research areas, he remains interested in an evolutionary analysis of this unique adaptation. Lignot hopes other investigators continue to search for the newly pinpointed cell type in other vertebrates.

This discovery offers fascinating insights into the adaptations that allow Burmese pythons to thrive in the wild. As our understanding of these adaptations grows, so too does our appreciation for the incredible diversity of life on Earth.

- The study of Burmese pythons' digestive systems has led to the discovery of a unique cell type, specifically adapted to process minerals found in bones, which could potentially have implications in health and wellness, particularly in supplements designed for medical-conditions related to chronic diseases such as chronic kidney disease.

- The findings from Jehan-Hervé Lignot's team suggest that fitness and exercise, particularly for individuals with respiratory conditions, could benefit from a deeper understanding of how Burmese pythons effectively digest whole prey, including bones, and extract essential nutrients.

- The identification of these bone-digesting cells in Burmese pythons, boas, and Gila monsters highlights the importance of nutrition in animals, and could potentially lead to advancements in our understanding of metabolic processes in different species, including humans.

- The complete dissolution of bones in python droppings, as observed by Lignot and his team, could spark further research in the field of science, particularly focusing on the efficient extraction of essential nutrients from food sources.

- As we continue to explore the incredible diversity of life on Earth, discoveries like the one made by Lignot's team serve as a reminder of the potential connections between seemingly unrelated biological processes, such as digestion and the absorption of minerals, and the broader field of biology.