Cholera: Causes, indications, and remedies

Cholera, an acute, infectious disease characterized by severe watery diarrhea and dehydration, remains a significant global health concern. The bacterium Vibrio cholerae, or V. cholera, is the culprit behind this disease, often spreading through contaminated food and water due to poor sanitation and hygiene.

Common risk factors for cholera include poor sanitation and hygiene, contaminated water and food, high population density and overcrowded settings, environmental factors such as extreme weather events, human mobility, complex humanitarian emergencies and conflicts, lapses in vaccination coverage, and socio-environmental vulnerabilities.

Prevention hinges largely on ensuring a safe water supply, improving sanitation and hygiene, vaccination in high-risk zones, and addressing socio-environmental vulnerabilities. Ensuring access to safe and clean water is crucial, with adequate chlorination of public water supplies and distribution of chlorine tablets to households being effective in reducing contamination. Improving sanitation and hygiene involves promoting proper waste disposal, preventing open defecation, and encouraging regular handwashing with soap.

Vaccination plays a key role in prevention, with oral cholera vaccines recommended in high-risk areas as part of comprehensive prevention strategies. Public health education is also vital, informing communities about hygiene practices, safe food handling, and the importance of clean water use. Targeted interventions in vulnerable areas, monitoring and preparedness for environmental changes, and addressing socio-environmental vulnerabilities further enhance control efforts.

Effective hygiene measures can help reduce the risk presented by cholera. This includes avoiding street food, ensuring water is bottled or boiled, and avoiding raw or uncooked food. Severe cases of cholera require intravenous fluid replacement, with an adult weighing 70 kilograms requiring at least 4 litres of intravenous fluids.

With proper care and treatment, the fatality rate from cholera should be around 1%. However, cholera affects between 1.3 to 4 million people each year and causes over 100,000 deaths worldwide. Prepackaged mixtures of oral rehydration solution (ORS) are commercially available but are often limited in distribution in developing countries.

There are currently three cholera vaccines approved by the World Health Organization: Dukoral, Shanchol, and Euvichol. All three vaccines require two doses to provide full protection, with Dukoral needing to be taken with clean water. Antibiotics can shorten the duration of the illness, but the WHO does not recommend the mass use of antibiotics for cholera due to the growing risk of bacterial resistance.

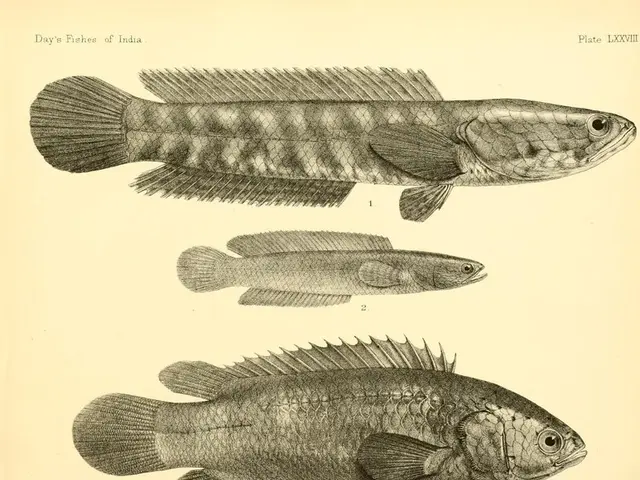

People most at risk of consuming food or water infected with V. cholera include healthcare workers, relief workers, travelers in areas with poor hygiene and food safety, and those without access to ORT and other medical services. Cholera can also enter through eating raw or undercooked seafood, particularly shellfish native to estuary environments, and through consuming poorly cleaned vegetables irrigated by contaminated water sources.

A doctor may suspect cholera if a patient has severe watery diarrhea, vomiting, and rapid dehydration. The most important treatment for cholera is oral hydration solution (ORS), also known as oral rehydration therapy (ORT). Weather changes, population loss, and improved sanitation can all end a cholera outbreak.

People with achlorhydria, blood type O, chronic medical conditions, and those without access to medical services are at a higher risk of a severe reaction to V. cholera. V. cholera bacteria can also live among the eggs of midges, serving as a reservoir for cholera bacteria.

In conclusion, understanding the risk factors and prevention methods for cholera is essential in combating this disease. By focusing on safe water supply, improved sanitation, hygiene education, vaccination in high-risk zones, and addressing socio-environmental vulnerabilities, we can work towards reducing the global impact of cholera.

- Alzheimer's disease, a common form of dementia, is a different medical condition from cholera, but it's important to remember that maintaining good health and wellness, including fitness and exercise, and proper nutrition can aid in overall health.

- In the context of cholera prevention, washing hands regularly with soap is an effective hygiene measure, similar to practices advocated for managing Alzheimer's, such as maintaining a nutritious diet and regular physical activity for the patient's overall health.

- Science plays a crucial role in understanding and tackling both Alzheimer's and cholera. For instance, research on the effects of COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) on the brain can provide insights into Alzheimer's pathology, while advancements in water treatment technology can help combat cholera.

- Just as people with certain medical conditions like diabetes or asthma need to take extra precautions, those with chronic medical conditions like achlorhydria may be at a higher risk of a severe reaction to V. cholera bacteria. Similarly, people with Alzheimer's may have unique health-related challenges that require special consideration.

- From a medical-conditions perspective, both cholera treatment (intravenous fluid replacement) and Alzheimer's management (medications and supportive care) require careful monitoring and professional intervention. While cholera treatment focuses on hydration, Alzheimer's treatment often involves managing symptoms and preserving a high quality of life for patients.