Alternate method of operation uncovered

When Katherine Kellogg embarked on her PhD research, she traded the lecture halls for the hospital wards, immersing herself in the heated debate over work hours for medical residents. This was far from typical for a management PhD student, but then again, Kellogg's project wasn't quite standard either. She delved deep into the contentious issue of reducing residents' workweek from a grueling 120 hours to a still-demanding 80 hours. Supporters claimed this change would prevent mistakes, while opponents feared it would lead to inadequate training.

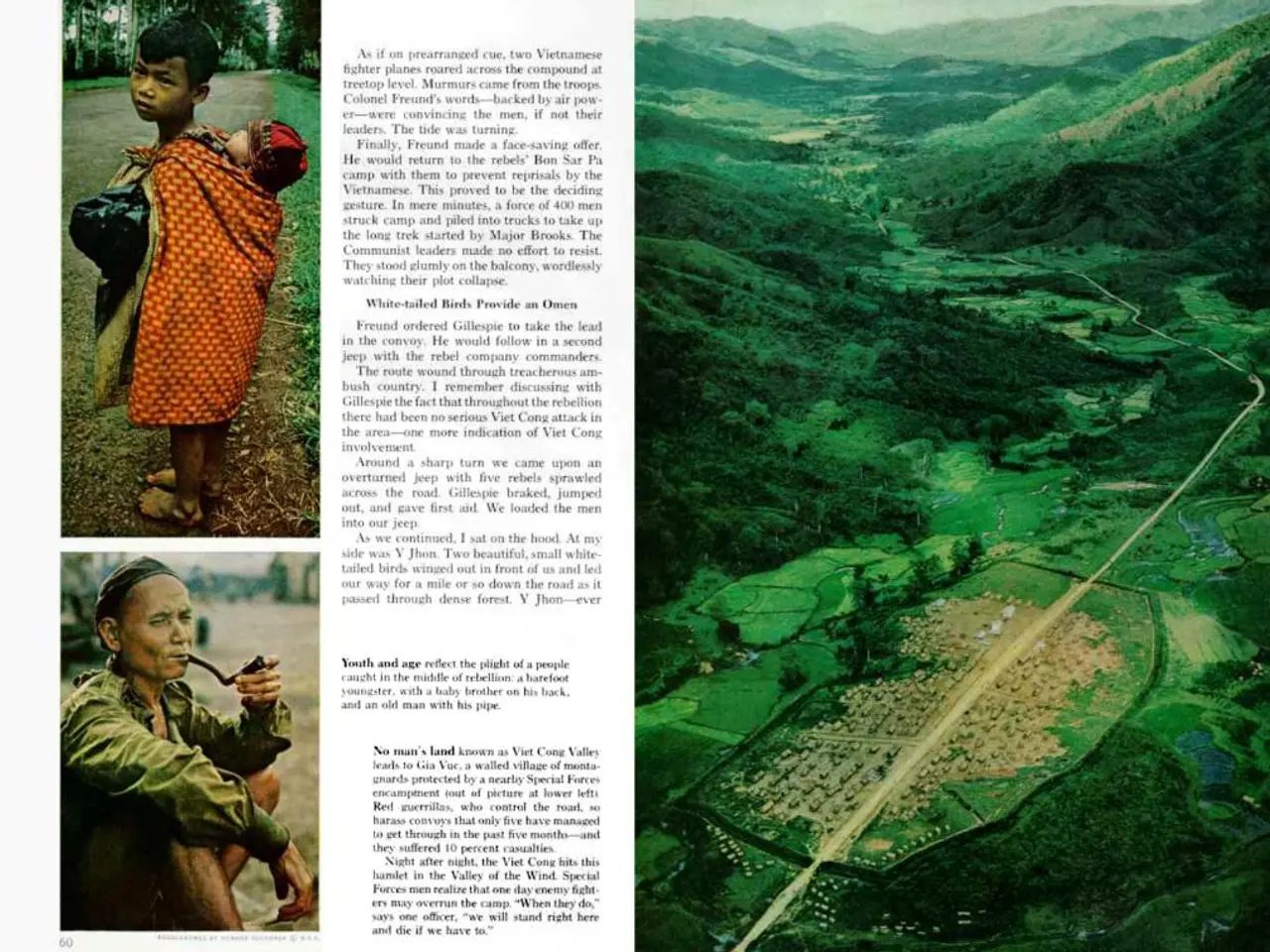

Kellogg's research was far from easy, given her own family commitments. With young children to care for, maintaining a resident's grueling schedule wasn't exactly a walk in the park, especially during those critical night shifts. "Perhaps I wasn't the brightest bulb to pick this particular group to study with young kids," Kellogg admits with a chuckle. "Not only did I need to put in the hours at the hospital, I also needed to be there every evening from 6 to 11 p.m. to observe how shift changes were managed."

Despite these challenges, Kellogg's research yielded fruitful results. She published a well-received book, "Challenging Operations," in 2011, detailing her findings. Her study focussed on three hospitals that agreed to reduce surgical residents' hours, but she found that only one of them had successfully implemented the change. Kellogg discovered that for policy changes to stick, reformers within institutions must collaborate and work tirelessly to shift the organization's culture on a daily basis; otherwise, changes may as well evaporate.

Kellogg's work helped pave the way for her tenure at the MIT Sloan School of Management, where she holds the position of Mitsui Career Development Associate Professor in Contemporary Technology. She continues to conduct on-the-ground studies of medical practices, employing an ethnographic method to live, observe, and understand the world her subjects inhabit.

Medicine has long held a place in Kellogg's career plans, although her path took some unexpected turns. As an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, she was a pre-med student who spent summers working in hospitals. However, she ultimately decided against pursuing medicine due to its hectic pace and lack of time for introspection.

Instead, Kellogg entered the world of consulting, working for Bain & Company and advising biotech firms. After earning an MBA from Harvard Business School, she joined the Red Cross as a manager overseeing blood-donor supplies in the Baltimore-Washington area. Yet, she found herself yearning for a more analytical role. Before long, Kellogg had enrolled in MIT Sloan's PhD program, where she seized the opportunity to conduct her thesis research within hospitals.

During her research, Kellogg uncovered an intriguing dynamic: Many trainees themselves resisted the idea of reduced hours, despite working 36-hour shifts and frequently dozing off during observation. Medical professionals steeped in the culture of medicine refused to budge, and many residents adopted their superiors' resistance. "They argue that shorter hours are not teaching people to always put the patient first," Kellogg explains, "and that there's something about learning surgery under intense pressure that will prepare them for anything." A gendered culture also played a role, with proponents of longer hours labeling reform efforts as "feminine" interventions in the tough world of high-pressure medicine.

Change in these rigid systems is not easy, but Kellogg believes it can happen if coalitions of workers have the opportunity to discuss and experiment with new working methods. This need for "relational spaces" within organizations is crucial for meaningful change, she contends.

Looking ahead, Kellogg has more medical research on her horizon. She is currently studying the "patient-centered medical home" approach, where patients are cared for by a team of medical professionals rather than strictly by doctors and nurses. This approach may reduce costs while maintaining high-quality care, she suggests.

Kellogg is examining the use of this method in both community health centers and one hospital, a project that thankfully spares her the exhausting night shifts in scrubs.

Insights on Organizational Change in Healthcare

- Resistance to Change: Healthcare professionals may resist change due to concerns about workload, patient care, and administrative burdens.

- Communication and Buy-in: Effective communication and garnering support from all stakeholders are crucial but often challenging.

- Involving Stakeholders: Involving all relevant stakeholders in the planning and implementation process can help ensure buy-in and address concerns early.

- Clear Communication: Clearly communicating the reasons for change, expected outcomes, and the process to all stakeholders is essential.

- Feedback Mechanisms: Establishing regular feedback mechanisms to monitor the impact of changes and make necessary adjustments is important.

- Lead by Example: Leaders should model the behaviors they expect from others and demonstrate a commitment to the change.

- Katherine Kellogg's research delved into the contentious issue of reducing medical residents' workweek, a topic far from typical for a management PhD student.

- Kellogg's study focused on three hospitals that agreed to reduce surgical residents' hours, but she found that only one of them had successfully implemented the change.

- Kellogg discovered that for policy changes to stick, reformers within institutions must collaborate and work tirelessly to shift the organization's culture on a daily basis.

- Kellogg uncovered an intriguing dynamic: Many medical trainees resisted the idea of reduced hours, despite working long shifts and frequently dozing off.

- Kellogg is currently studying the "patient-centered medical home" approach, where patients are cared for by a team of medical professionals rather than strictly by doctors and nurses.

- Involving all relevant stakeholders in the planning and implementation process can help ensure buy-in and address concerns early, as demonstrated by Kellogg's research.

- Clear communication regarding the reasons for change, expected outcomes, and the process is essential to gain support from all stakeholders, as seen in Kellogg's work.

- Leaders should model the behaviors they expect from others and demonstrate a commitment to change, a key lesson drawn from Kellogg's experiences in promoting organizational change in medicine.